Alpine Tips

Google maps pro tip - Full 3D in satellite view

Want to make Google Maps act like Google Earth, and view the whole world in fly around 3-D satellite view? Here's how to do it.

Here’s a very cool yet little known function in Google maps - Satellite view 3-D fly around, which makes Google maps behave pretty much like Google Earth. This is great for scoping out your next backcountry adventure. Super simple, here's how to do it.

(Open Google maps up a new browser tab and give it a try!)

Zoom into your favorite mountain in Google maps.

Change to satellite view by clicking the satellite icon in the lower left corner. (Yes, it still looks pretty useless, but wait, it gets better!)

Click the “3D” button in the lower right corner.

Hold down the control key on your keyboard, and left click and drag.

Use the scroll wheel on your mouse to zoom in and out. (Yes, a mouse with a scroll wheel is a big help here.)

This gives you complete 3-D viewing. Click the 2-D button to go back into "direct overhead" view.

Before this feature, the only way you could do this was to zoom around in Google Earth, which takes longer to load and has a bit of a learning curve to effectively fly around.

Mt. Adams (WA) in 2D Google maps, standard view, YAWN!

Mt. Adams in 2D Google maps, satellite view. More useful! Click "3D" in the lower right.

Now we're cooking! Zoom and pan around the mountain like Google Earth, to see the satellite view in 3-D.

How to make the "alpine quickdraw"

You want to avoid having gear dangling below your knees. So, how to rack those 60 and 20 cm slings? Answer: the “alpine quick draw”.

A good rule of thumb in climbing is to never let anything hang below your knees. But what do you do with a single /60 cm or double / 120 cm runner to shorten it up for racking?

Answer: the “alpine quickdraw”.

A simple trick is this method, best described with a photo. This triples up the webbing material, shortening your runner to a manageable length. You can clip to gear it tripled like this, or remove two of the three strands from one carabiner to use it at full extension.

(I learned this crafty trick decades ago, and still remember my fascination at seeing it for the first time. At the time I thought it was the really clever! Hopefully if this is new to you, you’ll think somewhat the same thing. :-)

1 - Start with a runner and two carabiners.

2 - Pass one carabiner through the other.

3 - Clip the bottom loop.

Done! A short and compact draw that hangs nicely on your harness, but is easy to deploy at full length.

Safety note: Having a rubber band or something similar to prevent the bottom carabiner on a sport climbing quickdraw from rotating is fine. But you never want to do this on an “open” sling, as the rope can easily become completely unclipped from the carabiner without you noticing. More details at this article.

Glissading - not always your best option for descent

Glissading - You might have learned how to do it on your first day of climbing school. It can be fun, save time, and your quads muscles in certain ideal situation. But there are also a lot of reasons why you may want to avoid it.

Glissading, the skill of (mostly) controlled sliding down a snow slope either sitting or standing, can be a lot of fun and save you time and legs on the proper slope. Pacific NW routes where this can work well include Mt. Hood south side, Mt. Adams south side, the Muir snowfield on Mt. Rainier, and various routes on Mt. Shasta.

Beginning climbers often learn this technique on day 1 of snow school, and then mistakenly think that it's something to be done at every opportunity. (And, hopefully you learned this on day 1 of snow school as well, but it's worth repeating: never glissade with crampons on!)

However, glissading has some serious downsides, and saving a few minutes on the descent may not always be worth it. Before you glissade, consider these points:

Much greater chance of injury than simply walking (usually a broken/sprained ankle, going too fast and cratering into a rock, talus or scree, or dropping into an unseen crevasse)

You wear out your gear faster (seat of your pants and pack bottom)

You get your butt wet

You can lose gear strapped to the outside of your pack, like trekking poles and crampons unless it’s very well tied down

Questionable time savings – saving 20 minutes on a descent by glissading may not mean so much when you weigh it against the downsides mentioned above, and the fact that a round trip climb may take 8-10-12+ hours.

LED “keychain” lights

Micro LED lights are handy to have around the camp, in your emergency kit, in the car glove box, in your chalk bag zipper pocket . . . They’re inexpensive, so might as well buy a multi pack.

image: https://www.amazon.com/Finware-Keychain-Flashlight-Batteries-Included/dp/B01GVJFBUW

Tiny ultra-light, single-bulb LED lights might look like a toy for a keychain, but they’re useful for far more than that. Get a few of them, they’re cheap!

They cast enough light to easily follow a trail in pitch dark, or find that rappel anchor heading down from a longer-than-planned alpine day.

Consider putting a shoestring on it, or it’s going to get hopelessly lost. A shoestring lets you to keep it comfortably around your neck, even when you’re sleeping. You could also girth hitch it to a loop inside your tent. Use it as an in-tent light rather than blasting your tentmate with your face-melter 300 lumen climbing headlamp.

Get one that has a switch to turn it on without holding constant thumb pressure on it - not all lights have this feature.

Make a “lantern” in your tent - turn on a microlight, put it on top of a water bottle, and then either tape it or put a sock over it to hold it in place. The light will diffuse through the water, casting a soft romantic glow over you and your smelly climbing partner.

Keep one in your first aid or survival kit for day hiking - no need to carry a heavy flashlight as a backup on hikes when an LED light will probably light your way out in an emergency just fine.

Buy a bunch, keep them in various places. Tape one inside your helmet if there’s room. Does your chalk bag have a zipper? Put one in there. Car glove box? Sure.

Here's an Amazon link to get 5 for just $9. If you have a few extras, give them to your pals.

Fix your broken tent poles

Do you have a broken tent pole? No problem, there’s a Northwest company that can fix it for you.

image: https://www.loopnews.com/

A company in the Vancouver WA area specializes in creating replacement tent poles for most any brand and size of tent.

Check ‘em out: Tent Pole Technologies

Use a “sparker” for lighting stoves

There’s one tool that you can always rely on to light your camp stove. And it's not a lighter or matches.

Lighters and matches don’t always work when damp or wet, and can break or malfunction – especially the cheap ones. Lighters can be less effective at altitude. Even if your stove has a built in igniter, they can be uncooperative; it’s best to have a backup way to light it.

A sparking device, aka “firesteel”, will always light your stove (gas or butane) or help make a survival fire. They have no moving parts, work when wet and at altitude. Weight, about 50 grams, cost about $20.

The simpler sparker models have a striker and a sparker, while a more upscale version has a small bar of magnesium included. Shave off a few bits of magnesium, add a spark, and you get a burst of almost 2,000 degree C flame.

The Swedish company Light my Fire sells high quality sparkers; a solid addition to your 10 essentials kit.

Sterling rope technical manual

What are the two chemicals you should always avoid getting on your rope? If a rope is wet, is it less strong, and by how much? Can I safely mark my rope with a Sharpie pen? Learn all this and more from the experts at Sterling, in their technical manual.

Think you know “the ropes”? The Sterling Rope Company has a great 16 page technical manual (.pdf file). Check this link and learn a few tricks.

(It's a 6 MB file, be patient on the download, it may take a few seconds.)

Learn about . . .

The difference between S twist and Z twist

Details of rope construction

The differences in manufacturing process between a static and dynamic rope

The five requirements of UIAA rope testing

The dramatic loss of strength that happens to a wet rope

The two chemicals you should ALWAYS avoid getting on your rope

The Word on marking your rope with permanent (Sharpie) pens

Sterling rope technical manual

Backup battery and charging cable - the 11th Essential

If you bring electronics in the backcountry, (smartphone and GPS app), it's pretty much mandatory to carry an extra power source. Here’s a great choice, at about 3 oz and $20.

Phones, watches, satellite communication devices, rechargeable headlamps . . . Most of us are carrying more important electronics into the back country, so it's crucial to have a means of charging them.

While always putting your phone in airplane mode at the trailhead to save battery is good practice, having some backup power is inexpensive and lightweight.

Here’s a very detailed article I wrote about battery saving tips in the back country.

Some people only will take an auxiliary battery on a multi-day trip. That works great provided you remember to charge your phone fully in your car driving to the trailhead, but that is a little task that's easy to forget. For me, it's more reliable to just carry a fully charged extra battery and cable as standard practice.

Anker and Nitecore makes great auxiliary batteries in a variety of sizes. With the larger batteries of modern phones, probably 5,000 mAh is the smallest you want to go, which should give you one full charge. (Geek note: “mAh” means milliamp hours, a way to describe battery capacity.)

The photo above is a few years old; now I'm using a 5000 mAh battery. but you get the idea. (Sharpie pen shown for scale)

If you're going on a longer trip, sharing your battery with partner(s) or don't mind carrying a little more weight, go with a 10,000 mAh battery. That can last last one person up to a week.

I like having both - a small one for short term emergency backup, and a 10,000 for longer trips.

A small auxiliary battery and charging cable together cost about $20, and weigh 3.5 ounces / 100 grams. Personally, I consider a battery and charging cable the 11th essential, and carry this tiny additional weight with me on every trip.

Cables . . .

iPhone Lightning. USB-A. Micro USB. USB-C . . . Aaaaaargh!

We all know that having 4+ different flavors of cables is a hassle! This is especially true when you're trying to minimize your gear. Let's hope the move to USB-C as a standard happens fast!

You can get a tiny 4 inch long charging cable for your iPhone; no need to bring the long cord you use at home. I'm sure there's one for Android folks as well.

Tip: cheap charging cables can get damaged getting banged around in your pack and fail when you most need them. Try to buy cables that are a little more durable, and consider bringing two of them on longer trips, they are inexpensive and extremely lightweight.

If you search online, you'll find loads of different battery options, many from off-brand companies. I’ve tried a few of these trying to save a few bucks, and been disappointed. I recommend you pay a tiny bit more and get a name brand like Anker or Nitecore.

Update: as of 2024, this is about the lightest weight and most compact 10,000 mAh charger on the market. I don't have one yet, but it comes highly recommended by some pro guide friends.

Steri-Strips for the first aid kit

Here's a great item to have in your first aid kit that most people don't carry.

Steri-Strips, a cross between a band-aid and a suture, are narrow strips of super strong first aid tape that really stick to skin and are used to close cuts in place of a suture. 3M makes them, so you know the adhesive is good stuff.

They're inexpensive, weigh nothing, and could save the day if you need to care for a substantial cut in the backcountry. Consider adding them to your first aid kit. Get them at better stocked pharmacies and medical supply stores, and through the usual online retailers.

Could this be the best free firestarter?

Want a terrific firestarter that’s free and burns great? Look no further than a supermarket - waxed cardboard produce boxes are your friend.

This tip is more for car camping or a home fireplace. For a superb fire starter, go to the produce section of any supermarket, and ask the produce person for a dark brown waxed cardboard box or two. (Or look around the back of the store and find a pile as shown below.)

These boxes are regular cardboard dipped in paraffin, so they can hold wet veggies like lettuce without falling apart. The boxes are free for the asking.

Tear the boxes into strips, and use them as starters for your next fire. They burn furiously for several minutes, are lightweight, mostly waterproof, and free. One box makes a LOT of fire starters!

Belaying the second from the anchor - pros and cons

Belaying a second can happen off your harness, or direct off the anchor. Learn the benefits of this technique - and one time to consider not using it.

Most climbers start out learning to belay off of their harness. For most snow climbs and most all instances of belaying a leader, this is still usually the best method. But for belaying a second when rock climbing, belaying directly from the anchor with either a Munter hitch or some version of an autolocking belay device has a host of advantages. Here’s a few of them.

Advantages . . .

better on difficult pitches (where fall is likely for the second), as it’s usually easier to catch and hold a fall

better for easy terrain (where second is moving fast and will likely not fall) as you can take in rope faster

puts less force on the anchor (only the weight of the second)

autolocks with Reverso, ATC Guide, or other modern belay devices (or just use a Munter hitch to keep it simple!)

belayer is free to move around more

easier to escape the belay and initiate a rescue

easy to rig a mechanical advantage haul to pull up the second if needed

easier to properly equalize the anchor toward the direction of load

Disadvantages . . .

fall directly impacts anchor (rarely a problem on rock if the anchor is stout.)

So, when might you want to belay the second off of your harness? Basically, when the anchor is anything less than 200% solid.

That means most of the time when you are snow climbing, and in many alpine rock climbing situations. When climbing alpine rock (which typically means many pitches over a long day and trying to move as efficiently as possible over relatively easy climbing) an "anchor" might be one decent cam plugged into a crack, or a sling around a small tree or over a rock horn, or some other single point of gear.

In this case, the belayer will typically sit down, try to brace their feet in a solid position, and belay off of their harness. By doing this, the belayer takes the impact force for any fall onto them, and the anchor is essentially backing up their stance.

Note: if you choose to use an auto locking blade device such as an ATC Guide or Petzl Reverso, keep in mind that there have been many serious accidents when people use these devices in correctly, often when trying to lower someone when the rope is under load. Be absolutely sure you know how to use these devices correctly before ever trying it on a real climb.

image: “Multi-Pitch Belaying- Potentially Fatal Errors to Avoid” - youtube.com/watch?v=s9np7B1Zao4

Belayer’s responsibilities to the climber

The belayer has a LOT more to do than it may first appear. Do you know all of these duties? Did I leave any out?

The belayer has many duties beyond feeding out or taking in rope. A good belayer, when belaying either a leader or a second, will consider doing the following:

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Spotting-and-belaying-at-the-start-of-the-route?ActivityName=Rock-climbing

Belaying the leader, most important! If you're on the ground, spot the leader before (or even after) they make the first clip! No need to “belay” if there’s no gear in. This usually means the belayer drops the rope and stands with hands outstretched, ready to keep the leader’s head and upper body from smacking anything if they fall before clipping the first piece of gear. The moment the leader clips the first pro, the belayer drops their hands to the rope and starts the belay properly. Keep your thumbs tucked in and your fingers together (aka “spoon”), and not fingers spread out (aka ”fork”) to avoid injury.

If you are with a new partner and top roping, ask how much slack is desired. Many beginners want you to keep the rope fairly tight, while more experienced people will probably want a little slack.

Never pull the leader off by keeping rope too tight! Always gives them a meter or so of slack rope so they can move freely. If the leader is climbing above a ledge, you can snug it up the rope a little, but never restrict their movements.

Be attentive and watch; feed rope if they need to clip, take rope in if they are looking sketched.

Keep the rope out of the leader’s way before the first clip. This may mean you stand off to one side to keep the rope away from their feet.

Help build a multidirectional first gear placement, if needed.

Give encouragement to the climber, but avoid idle chatter. Keep your communication as short and clear as possible.

Tell leader about rope getting stuck in cracks or around horns (“flip rope”).

Warn leader (“grounder alert”) if they have climbed too far above their last piece of gear.

Tell leader about amount of remaining rope if it’s getting close to the end. Use the call, “feet 2-0”. (Most belayers underestimate the amount of rope left.)

Make sure the rope feeds freely. Flake the rope well, and watch for tangles. Tarps, rope bags or duffel bags are good for this.

If you're on a single pitch climb and plan to lower your leader, be sure the middle mark of the rope does not pass through your belay device, and you have closed the rope system by having a knot in the end of the rope. These steps prevents the common accident of dropping your climber when lowering because your rope is too short.

Tell leader if they back clip (more of an issue when sport climbing, not a concern with long runners).

When belaying the second up to your stance, as the second approaches the anchor, the belayer tells them two things: 1) where to clip and 2) where to stand.

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Spotting-and-belaying-at-the-start-of-the-route?ActivityName=Rock-climbing

Slinging a boulder for an anchor - two cautions

When you put a sling around a boulder for an anchor, the angles can get wide very easily, magnifying the load.

A common anchor on alpine routes is the simple sling around a boulder or rock spike. Even though the boulder itself may be super solid, there are some things to watch for when using this method.

1) Check the boulder carefully all the way around for any sharp edges. A new sling that can hold 20kN can cut very easily under tension combined with the sharp edge of rock or a crystal.

2) A short sling around a large boulder may make a wide angle in the sling that put a larger-than-ideal load on the sling material. (An angle of 90 degrees or less is the rule of thumb, and 60 degrees or less is ideal). Solution: Use a longer sling to make the anchor angle smaller. The diagram below shows how a small change in sling angle and greatly increase the forces on your anchor.

The diagram is from the excellent book "The Complete Guide to Climbing and Mountaineering" by Pete Hill.

DIY - Mark your tent stakes for easier tracking

Dang, those little tent stakes are easy to lose if you put them down for a moment and don't remember where. Here’s a tip to help them stay found.

How many of you have had this situation happen? It’s early in the morning and you’re about to strike your tent. You casually pull the stakes, maybe toss them on the ground, rocks, snow. After the climb you get home and find you now have 7, not 8 stakes. Here’s two tips to help you out.

1) Spray paint part of each stake for easy visibility. A clean way to do this without having to hand hold each stake is to get a piece of scrap cardboard from a box. Make a small hole or slit in the cardboard for each stake. Shove about 3/4 of the stake through the cardboard. Spray paint one to two coats of some kind of easy to see color on the top of the stake. Day-Glo Orange is a good choice, as its easier to spot. Rustoleum brand works well.

2) To make sure you don’t lose any, store them in a Zip-lock bag and write the amount of stakes in the bag on it with an indelible marker. That will make a no-brainer out of the “how many stakes did I bring" question.

Is it a knot, hitch, or bend?

Does every climber need to know these definitions? No. But for the Type A personality, (which is probably most of us climbers) the difference between these three different terms is actually quite interesting.

Not all “knots” are true knots. Technically, a true knot is capable of holding its form on its own without another object such as a post, eye-bolt, or another rope to anchor it.

Example: Figure 8 on a bight

A hitch, by contrast, must be tied around something to hold together; remove the thing it’s tied to, and a hitch falls apart.

Example: clove hitch. Unclip this from the carabiner, and you don't have a knot at all.

A bend is a knot used to join two rope ends. Example: flat overhand bend

(Formerly known as the "EDK", or "European Death Knot"; let's not use that term anymore, OK?)

In practice, we use “knot” as an umbrella term to cover all these types, but the distinction is useful to know.

If the context makes it unclear what you mean, you can use the term “hard knot” to distinguish a true knot from a hitch or bend.

Shorten a sling with carabiner wraps

Sometimes, to better share the load on an anchor, it's helpful to shorten a sling just a centimeter or so at a time. Here's a nifty way to do it.

Often it's handy to temporarily shorten a sling or cord by just a cm or two, typically done when anchor building. Doing this can help fine-tune anchor load distribution by shortening the arm that's going to your strongest piece, adjust a cordelette if the direction of pull has changed a bit, or shorten one sling if the bolts you’re clipping are not quite in the same horizontal plane.

One easy way to do it is to simply wrap the sling a few times around the carabiner. With a skinny Dyneema sling like this, each wrap shortens the sling about 2 cm.

Probably best not to use more than two wraps. If you need to shorten your sling more than that, it’s probably time to rerig your anchor.

Other methods: put some twists in the sling, or tie a clove hitch.

Safety note: Don’t do this unless you're dealing with a completely static anchor. If you do this on lead the sling loops can loosen in such a way as to slip down over the gate and then when loaded can open the gate. That may be hard to visualize, but if you take the setup below, and jiggle it around a bit as might happen on a long pitch, and then just keep randomly loading it, one of those extra wraps could loosen up, slide around, and potentially open the gate.

2023 Update:

I’ve received a few frosty comments on this technique over the years, most of them saying something along the lines of “this is going to weaken the carabiner, because you're putting the load closer to the gate”, or something like that.

I was curious if this has any merit, so I had my buddy Ryan at HowNot2 test this. Guess what?

It DID NOT weaken the carabiner

It DID weaken the sling.

Ryan did two different break tests on this with a Dyneema sling. First test the sling broke at 12.4 kN, the second test is broke at 15.4 kN. The sling was rated (I think) 22 kN.

Would this be different with nylon? Probably. Is this concerning? Maybe. Does it concern me? Not really, because these numbers are still significantly higher than you're ever going to see in any recreational climbing situation. But it’s still an interesting data point that I wanted to share.

I don't think I can embed this short form YouTube video in my webpage, so here's a link to see it yourself.

Screen grab from Ryan's video is below.

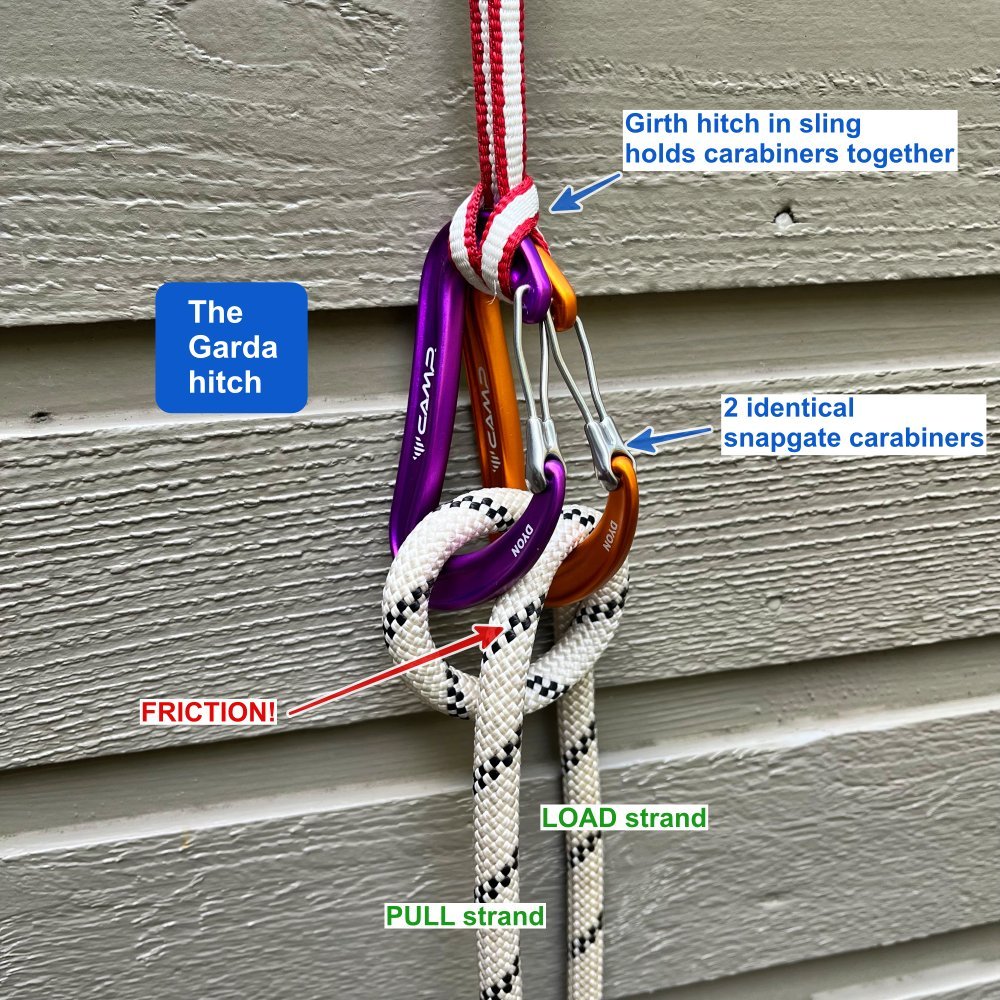

Pros and cons of the Garda Hitch

The Garda hitch is an old-school method to make a one-way ratcheting knot. This can occasionally be useful for hauling a light load, and in some self rescue scenarios. However, it does have a few significant downsides, and there are some modern tools that can usually do the job better.

Do you need to haul a small load? Did you forget your Petzl Traxion or Tibloc? Might be time to break out the old-school Garda hitch, aka “alpine clutch”.

The Garda hitch is a one-directional, self-locking hitch that lets you haul, but lets you relax your grip when you need a break, capturing your hauling progress.

To haul, simultaneously pull UP on the load side of the haul rope and DOWN on the brake side of the rope. Don’t just pull down on the brake side, because the garda hitch adds a LOT of friction. An informal test I did with a spring scale and a 10 pound barbell weight showed it took about 60 pounds of pulling force to lift a 10 pound weight through a Garda hitch; just 17% efficient. That is terrible!

The Garda hitch can work (reasonably) well when you create slack from doing something else, and then pull the slack rope through the hitch. If the rope has any kind of load on it, it's going to be very difficult to pull through. So, be sure you lift UP on the load side, and not just pull DOWN on the brake side.

Locking the knot is simple: just let go.

A few notes:

Ideally, use identical snapgate carabiners. Some people think it works better with oval carabiners, but personally I don't think they make much of a difference. You can hang two quickdraws together and use the bottom two carabiners.

Avoid locking carabiners with a sleeve, as the sleeves can prevent the rope from locking down properly.

Adding the girth hitch from the anchor sling is optional. But, in my experience having the top of the carabiners held together makes the hitch better behaved. Try it with and without and go with what works for you.

While some sources suggest this can be used in a crevasse rescue operation as the progress capture, many folks think this is not such a great idea because the hitch can be a little squirrely if the carabiners are not properly oriented, it's hard to release under load, and depending on how it's configured, it can add a LOT of friction to your hauling system. The few times I've used it, it's been for non-critical situations such as hauling up a backpack. (Having said that, I recently went to a crevasse rescue clinic taught by a pro guide, and he used a Garda as a progress capture in a 6:1, creating slack and then capturing it with the Garda.)

It's important to monitor the Garda hitch carefully. If you get a loop of slack rope above the carabiners, weirdiosities can happen and the entire thing can unclip itself! Yikes! (Another reason why I am not a fan of this for rescue purposes. )

Downsides to the Garda hitch:

Lots of friction. Yes I mentioned that, but it's worth mentioning again.

Very difficult to release under load.

A bit tricky to remember which is the load strand and which is the haul strand.

Depending on the carabiners used, it can be a little wonky and unreliable. Adding a girth hitch to squeeze the tops of the carabiners together, as shown in the previous photo, can help with this.

This hitch works best if the carabiners are hanging free instead of lying against the rock. When you start hauling, the rope will run along the spine of the carabiner, see photo below. If the carabiners are resting against the rock, it could have the rope rubbing against the rock, creating extra friction, or even do something weird to the carabiners or so they don't “lock” together as you expect them to.

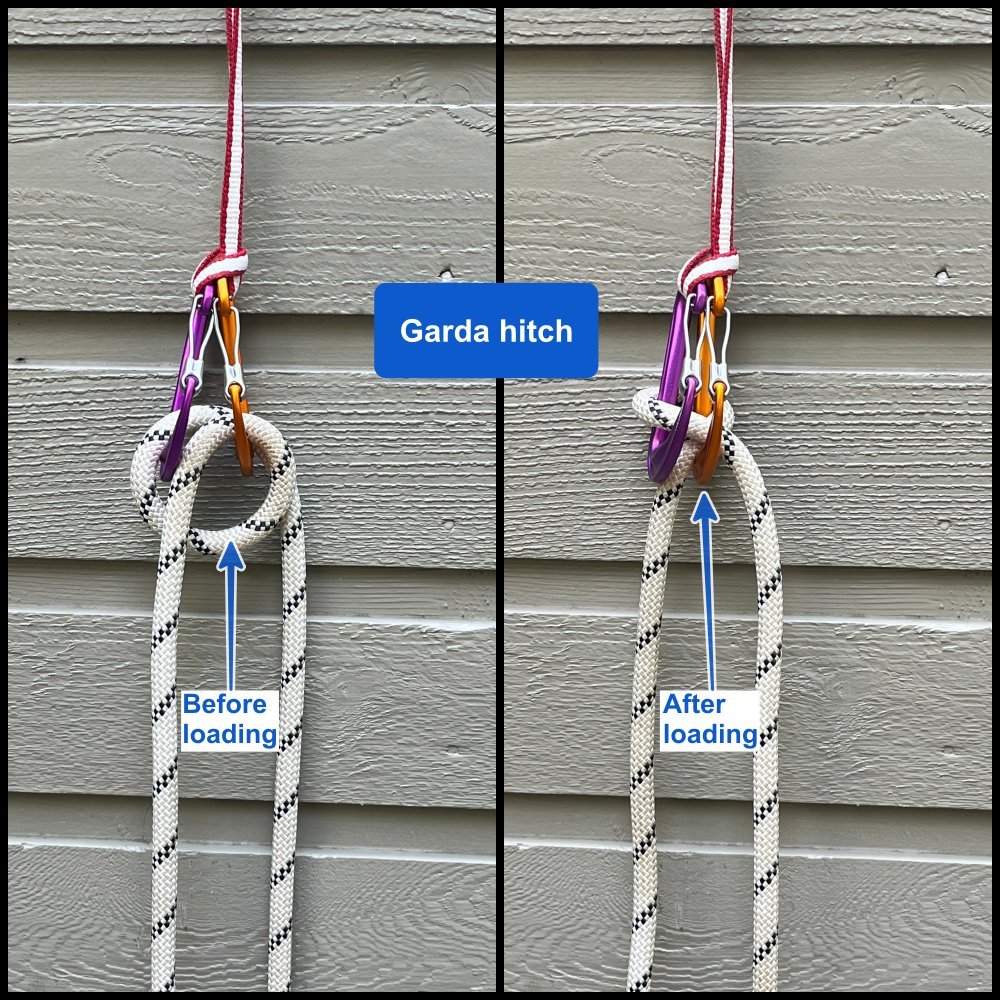

It usually flips after it’s loaded and looks completely different than how you originally tied it, which is a little unnerving! There is no other climbing knot that does this. See photo below.

Having said that, it can be used for crevasse rescue; in this case, to ascend a rope. Here's a great video on crevasse rescue techniques from some top German guides. Watch the video below, starting at around 3:15, to see the demonstration..

Here's how to tie it.

Start with two identical carabiners (non-lockers preferred) clipped to the anchor, gates facing down and out. Clip the rope through both carabiners.

In the photo below, the hauling rope is on the left (purple carabiner) and the loaded rope is on the right (blue carabiner).

in the haul strand of the rope on the left, make a loop as shown.

Clip this loop into the right side carabiner.

Done. If you've tried it correctly, the haul strand should be coming down between the two carabiners. Pull on this, and the load will come up. If you stop pulling, the load tensions the carabiners together, pinching the rope.

Keep your water from freezing in a snow camp

Camping in sub freezing conditions? Drinking water is a valuable commodity. Here's how to keep it from freezing.

When you're in a frozen environment like a Denali high camp, liquid water is precious. After you melt snow, preserve that water by burying your pots of water.

You need a pot of water, a stuff sack or large plastic bag that goes over the pot (this is essential to avoid frozen ice against the pot the next morning), four wands, and a shovel. Bury your pot about 10 inches below the snow’s surface and cover it with snow (if powder is not available, use the shovel to pulverize snow as much as possible). It is key not to leave any air pockets. Use the wands to locate it the next morning. Even if it’s 60 below, your water will not be frozen! This works with water bottles as well, but you might have to bury those a bit deeper.

More tips:

If your water is in bottles, store those upside down so any ice, if it starts to form, will do so on the bottom, not the lid.

To keep the cap from freezing to the bottle you can coat the threads of your bottle with vaseline or lip balm.

If you have a platypus-type bottle, you can wrap the tube in foam insulation, and be sure to blow water back into the bladder after you take a sip so it won’t freeze in the tube. (Better yet, don't take a water bladder in the first place, they are prone to all kinds of problems when alpine climbing.)

If the water bladder water line freezes, just put the line under your jacket next to your skin (not as bad as it sounds, really!) Your body heat will melt the ice in a few minutes.

Get water on the go - 3 tips

Climbing on snow or hiking near mountain creeks? Here’s 3 tips to keep to you hydrated.

Here are some tips for “water harvesting” on the move.

1 - If climbing or hiking across a snowfield, keep your water bottle easily accessible. Frequently add handfuls of snow to your water, without stopping. On a warm, sunny day, this snow will melt or form a drinkable slush — bring a straw and some Gatorade powder for a poor-man’s Slurpee. (One more reason not to use a water bladder - you can't easily refill like this.)

When you grab or cut snow chunks to add to your water bottle, collect from the bottom edge of a snowfield or serac. This snow is heavily saturated with percolation and will add more water than the same snow volume gathered from lighter, fluffier snow.

2) Water running down a rock face face in a broad, yet shallow, curtain can be hard to collect. Here’s 2 tricks.

A - Carry a small length of aquarium tubing type hose; buy it any a decent hardware store or aquarium shop. Use it as a flexible straw to suck up water that you can't reach. (This is especially handy in desert areas, where water may be just a tiny trickle.)

B - Remove your jacket and long-sleeved shirt, and then spread and flatten your hand across the rock, giving the wet slab a chest-level “high-five.” The water will collect on your fingers and run down to your elbow in a stream; fill your bottle from this drippage point. (This last tip and image are from Climbing magazine.)

Face your tent door into the breeze to avoid bugs

Mosquitos. We all hate ’em. Here's a tip to help keep them at bay.

When it’s breezy, mosquitoes will congregate on the lee side of objects to avoid being blown away. So pitch your tent door into the breeze. You’ll be able to enter without bringing the swarm in with you.

Ridgelines often have more wind than hollows or valleys. If it's really buggy, try to camp on a ridgeline if you can.

Face the door of your tent toward an oncoming breeze to help avoid mosquitoes.