Alpine Tips

Innovative Gear - Aideer Climbing

Aideer Climbing is a one-man show, crafted by Olle Hjort in Stockholm Sweden. Olle makes soft good for aid climbing, big walls and some industrial use.

This section of my website highlights small companies, inventors, artists and other superb humans who make exceptional climbing-related gear.

If you know a company that wants to be on these pages, please let me know.

I don't get any sort of advertising fees / benefits / kickbacks from these pages. I simply want to showcase cool companies to a wider audience.

Occasionally these companies may give me a product to review. If that happens, I’ll tell you.

Listings are alphabetical.

Aideer Climbing - Olle Hjort

Aideer Climbing is a one-man show, crafted by Olle Hjort in Stockholm Sweden. Olle makes soft good for aid climbing, big walls and some industrial use.

Aider Climbing website.

Preferred way to connect and order is through Instagram, @aideerclimbing

Olle was kind enough to send me a pair of his aid ladders for review, and they are beautiful! Sturdy in all the right places, lightweight in the other places, and literally half the weight of my older workhorse ones.

(If you’re lucky, or ask nicely, he might even sew a cool Swedish flag on for you.)

Currently, Aideer offers the following products:

aid ladders (let’s not call them “etriers” - French for “stirrup” - anymore, okay?)

Russian aiders (VERY cool and hard to find!)

big wall gear sling

“Collector of Dropped Objects” (CODI), a sort of large hanging basket designed to be strung below people who work at heights so they don't drop stuff

A few of his schweeeeeet aid ladders, ready for shipping.

If you're ready for battle on your next steep, scary big wall, you might want a pair of Russian aiders. They are very different than the standard ladders shown above, and Olle is one of the few people who makes them.

More for industrial use, here is the CODI (Collector Of Dropped Objects). If you're doing industrial type work where you don't want to drop anything, hanging this below your job site could be a fine idea.

Innovative Gear: Avant Climbing Innovations

Avant Climbing Innovations, based in Flagstaff Arizona, and founded by Brent Barghahn, focuses on specialty gear for top rope and lead rope solo climbing.

This section of Alpinesavvy highlights small companies, inventors, artists and other superb humans who make exceptional climbing-related gear.

If you know a company that belongs on these pages, please let me know.

I don't get any sort of advertising fees / benefits / kickbacks from these pages. I simply want to showcase cool companies to a wider audience.

Occasionally these companies may give me a product to review. If that happens, I’ll tell you.

Listings are alphabetical.

Avant Climbing Innovations founder Brent Barghahn free climbing El Corazon (5.13), El Capitan.

Avant Climbing Innovations, based in Flagstaff Arizona, makes specialized gear focused on top rope solo and lead rope solo climbing.

Avant Climbing Innovations website

Avant Climbing Innovations Instagram, @avant_climbing_innovations

Brent’s website and blog, with nice articles and photos of his adventures

Avant Climbing Innovations was founded by Brent Barghahn. Brent, a product designer, professional climber and humble bad-ass, knows a thing or two about hard climbing on big walls. He has some very impressive free ascents on El Capitan, such as El Corazon, El Nino, and Golden Gate. He is also an leader in spreading the gospel of proper technique and gear for lead and top rope solo technique. Oh yeah, and he has a few patents as well!

Top rope solo neck lanyard - If you ever done top rope soloing, you might've tried the DIY method of some sort of DIY bungee cord thing around your neck. This adjustable neck lanyard works a lot better.

Snack Pack multi pitch storage pouch - If you want to leave your backpack on the ground, but still have some room for a few essentials like snacks, phone, windbreaker, and headlamp, check this out. It's basically a smartly designed chalk bag with a nice closure and zipper to store a few extra goodies; plus it has a phone tether.

Flex-Link Anti-Crossload Protector - Cross loading your carabiner is not a good thing, especially when you’re rope soloing. This clever device keeps this from happening, and it looks like it could be helpful in lots of cases other than rope soloing.

Top Rope Solo Neck Lanyard

image: https://avantclimbing.com/

Snack Pack multi pitch storage pouch

image: https://avantclimbing.com/

Flex-Link - Anti-Crossload Protector

image: https://avantclimbing.com/

Learn more about Brent from these videos.

Great documentary video produced by Arc'teryx with Brent free climbing one of the hardest routes on El Capitan with Amity Warme.

An interview with Ryan Jenks of hotNOT2.com, with a deep dive into top rope solo technique.

Innovative Gear - Frn Collective

Frn Collective was founded by Jordan Cooper. Jordan crafts unique clothing and climbing products made from repurposed climbing ropes.

This section of Alpinesavvy highlights small companies, inventors, artists and other superb humans who make exceptional climbing-related gear.

If you know a company that belongs on these pages, please let me know.

I don't get any sort of advertising fees / benefits / kickbacks from these pages. I simply want to showcase cool companies to a wider audience.

Occasionally these companies may give me a product to review. If that happens, I’ll tell you.

Listings are alphabetical.

Great choice for a workshop if you ask me. Frn Collective founder founder Jordan Cooper working on a rope belt.

Jordan Cooper is the founder of Frn (like the plant) Collective, a one man operation based in Salt Lake City. Jordan makes hand crafted belts, chalk bags and more from repurposed climbing ropes.

Frn Collective website

Frn Collective Instagram @frn.collective

Don't get me wrong, I think a dog leash made out of an old climbing rope is a pretty good application. But if you get a bit more creative, you can do a lot more with the colorful rope sheath.

A cool belt made from a pair of retired rope sheaths.

Nice chalkbag!

Keychains, anyone?

Matching leash and dog collar, sign me up!

Innovative Gear - Gear Perspectives

Gear Perspective, from Kingsburg California, specializes in gear for canyoneering. Several of their products cross over well to alpine climbing and ski mountaineering.

This section of Alpinesavvy highlights small companies, inventors, artists and other superb humans who make exceptional climbing-related gear.

If you know a company that belongs on these pages, please let me know.

I don't get any sort of advertising fees / benefits / kickbacks from these pages. I simply want to showcase cool companies to a wider audience.

Occasionally these companies may give me a product to review. If that happens, I’ll tell you.

Listings are alphabetical.

Good canyoneering gear can take you to some amazing places like this . . .

Gear Perspective, based in Kingsburg California near the beautiful central Sierra Nevada, has a focus on gear for canyoneering.

Gear Perspective website

Gear Perspective Instagram, @gearperspective

Here are some of their more popular offerings.

Micro 30 RADlineRope bag - This bag is the perfect size for 30 meters of 6 mm cord, such as the Petzl RADline. This makes it very helpful for Alpine climbers as well as canyoneering. It has double grommets in the bottom so you can tie a fixed loop, very handy for crevasse rescue. It was designed with collaboration from IFMGA guide Dave Searle, so you know it's solid. Gear Perspective gave me this bag for review, and I love it. They also make a larger version for a 60 meter 6 mm rope, if you have a longer tagline. (On their website it's under the “Search and Rescue” category.)

Shoulder / belt pouch - This is another one of their products that crosses over to climbing and backpacking. Keep your phone, energy bar, folded map and other essentials at the ready on your shoulder strap. Comes in lots of fun colors!

Double end rope bag V2 - Canyoneering folks have long realize the benefits of rope bags to keep your life tangle free. Some techniques benefit from having access to both ends of the rope in the bag, and this is designed for that.

60 meter and 30 meter rope bags (here, with 6mm rope)

Shoulder / belt pouch

Double end rope bag

image: https://gearperspective.com/

Innovative Gear - High Mountain Gear

High Mountain Gear is from Tacoma Washington. Founder Kyle Willis designs and sews small batch made-in-USA products for alpine and big wall climbing, much of it from re-purposed fabrics.

This section of Alpinesavvy highlights small companies, inventors, artists and other superb humans who make exceptional climbing-related gear.

If you know a company that belongs on these pages, please let me know.

I don't get any sort of advertising fees / benefits / kickbacks from these pages. I simply want to showcase cool companies to a wider audience.

Occasionally these companies may give me a product to review. If that happens, I’ll tell you.

Listings are alphabetical.

High Mountain Gear founder, Kyle Willis

High Mountain Gear is a small-scale gear manufacturer in Tacoma Washington. Founded by Kyle Willis, HMG makes some very cool products for big wall and alpine climbing.

High Mountain Gear website

High Mountain Gear Instagram, @highmountaingear

Kyle is a master at sewing and designing. He strives to use as much recycled and repurposed material as possible, such as extra sturdy sailboat sails.

HMG’s most innovative gear is the Taco portaledge system, the lightest portaledge (and fly!) currently available. Kyle was nice enough to send me one for review, and it's quite amazing. It's a sort of envelope into which you insert a Thermarest-style inflatable sleeping pad, and it's surprisingly comfortable.

High Mountain Gear also makes rope bags, which is pretty much mandatory to keep 6 mm tagline tangle-free. What I really like about his rope bags is the stiffness of the fabric, which keeps the mouth of the bag wide open when you're stuffing the rope, a big timesaver.

Related to the rope bag is the HMG ice screw cannon, a great way to store all of your screws and without them gouging anything else in your pack.

The Ski Guide Sled Tarp is an emergency shelter, and a way that you can hopefully drag out your injured partner if needed. Hopefully you don't need it for either one but if you do, you'll be glad you have it.

Check out some of their products below.

The Taco portaledge system

The High Mountain Gear rope bag - a perfect fit for 60 meters of 6 mm skinny rope

The HMG ice screw cannon

The ski guide rescue tarp

Innovative Gear - Hyalite Designs

Hyalite Designs is artist Katie McKinstry Stylos. Based in Montana, Katie creates amazing mountain landscape art from repurposed climbing rope.

This section of Alpinesavvy highlights small companies, inventors, artists and other superb humans who make exceptional climbing-related gear.

If you know a company that belongs on these pages, please let me know.

I don't get any sort of advertising fees / benefits / kickbacks from these pages. I simply want to showcase cool companies to a wider audience.

Occasionally these companies may give me a product to review. If that happens, I’ll tell you.

Listings are alphabetical.

Hyalite Designs founder Katie McKinstry Stylos in the studio.

Hyalite Designs is Katie McKinstry Stylos. She’s a Montana-based artist who creates unique and beautiful landscape art from repurposed climbing ropes.

Hyalite Designs website, including gallery of previous work

Hyalite Designs Instagram, @hyalite_designs

Katie designs and creates one-of-a-kind mountain scenery art from retired climbing ropes.

She lives near the ice climbing mecca of Hyalite Montana, and when she's not in her studio, you can probably find her climbing up frozen water in the nearby canyons.

Instagram is a great place to see more of her art and find out how you can buy one yourself. (I don’t yet own her art, but I certainly hope to someday.)

Here are some photos of her art, from her website and Instagram.

Innovative Gear - Moses Enterprises

Based on the central California coast and founded by Theron Moses, Moses Enterprises as an expert manufacturer of custom big wall hardware like cam hooks, Tomahawk pitons, and more. Don't start up a big wall without these goodies!

This section of Alpinesavvy highlights small companies, inventors, artists and other superb humans who make exceptional climbing-related gear.

If you know a company that belongs on these pages, please let me know.

I don't get any sort of advertising fees / benefits / kickbacks from these pages. I simply want to showcase cool companies to a wider audience.

Occasionally these companies may give me a product to review. If that happens, I’ll tell you.

Listings are alphabetical.

That is one impressive collection of big wall hardware!

Theron Richards is the man behind Moses Enterprises, a California central coast based designer and manufacturer of specialized big wall hardware

Moses Enterprises website

Moses Enterprises Instagram @mosesclimbing

Theron is an expert machinist and metal worker. His gear is considered mandatory for many modern aid routes.

One of his most popular products is the iconic Tomahawk beak style piton. This is hammered into very thin cracks on traditional aid routes. You can also hand place them over existing features like small constrictions and broken off copperheads.

Another great product is the classic cam hook. These are great for clean aid climbing because you can place them in a thin (usually vertical) crack, watch them magically cam as you put weight on them, letting you make very rapid progress up what used to be slow travel. Again, pretty much mandatory gear on any big wall. (Personally, I have a couple of cam hooks usually tied onto my ladders.)

Tomahawks, cam hooks, Logan hooks, and rivet hangers

(generously donated to folks helping with a cleanup in Yosemite, nice!

For connoisseurs of the aid climbing dark arts, Moses offers copperheads and various flavors of chisels.

Innovative Gear - RopeLite

RopeLite is Douglas Ray, a Seattle-based climber who makes spliced lightweight specialized cordage for climbers and rope rescue applications.

This section of Alpinesavvy highlights small companies, inventors, artists and other superb humans who make exceptional climbing-related gear.

If you know a company that belongs on these pages, please let me know.

I don't get any sort of advertising fees / benefits / kickbacks from these pages. I simply want to showcase cool companies to a wider audience.

Occasionally these companies may give me a product to review. If that happens, I’ll tell you.

Listings are alphabetical.

RopeLite founder Douglas Ray

Douglas makes specialized and extremely lightweight friction hitch cords, bridles for carrying a litter, and more. Because the ends often have a spliced eye and not sewn in a loop, his equipment offers a great strength to weight ratio.

He also does custom orders. If you need something cool that he doesn't sell, get in touch.

Doulas sent me a hitch cord to review, and it's pretty impressive. It makes a solid friction hitch on 6 mm Petzl PURline, which is notoriously difficult to use with most friction hitches.

Here are some photos of RopeLite gear, from Douglas’ Instagram and website.

RopeLite Technora hitch cord

Adjustable litter bridle

Custom project for crevasse rescue

5 meter piece of cord with a 25 cm spliced loop on each end. Each end loop can make a prusik on ropes as small as 6mm. Or you can make a friction hitch anywhere in the middle. Weight: only four ounces / 113 grams

Innovative Gear - Skot’s Wall Gear

Skot's Wall Gear is the one man show of Skot Richards, a big wall expert and California-based designer and producer of big wall climbing gear. His Alfifi is a near mandatory gear for aid climbers.

This section of Alpinesavvy highlights small companies, inventors, artists and other superb humans who make exceptional climbing-related gear.

If you know a company that belongs on these pages, please let me know.

I don't get any sort of advertising fees / benefits / kickbacks from these pages. I simply want to showcase cool companies to a wider audience.

Occasionally these companies may give me a product to review. If that happens, I’ll tell you.

Listings are alphabetical.

Skot Richards, in action on El Capitan

Skot Richards is a one person, California-based designer and producer of big wall climbing gear.

Skot’s Wall Gear website

Skot’s Wall Gear Instagram, @skotswallgear

Skot is a multi talented guy! A veteran of many El Capitan climbs, he designs, sews, and does metal and machine work to constantly improve his products.

His flagship gear is the Alfifi, which is a combination adjustable tether and stout steel hook. This makes many different aspects of aid climbing faster and more efficient, such as top stepping, cleaning traverses, and even leading without connections to your ladders.

Skot sells some key gear to dial in your 2:1 hauling system, such as the perfect length of low stretch Zed cord, and a zero-stretch wire quickdraw. (Side note: here's my detailed article about the 2:1 haul system.)

He also offers the service of custom sewn webbing loops onto your hooks, which is something you probably don't realize you need until you try his.

Skot also offer several flavors of aid ladders, with the nice design feature of a designated clipping point for your tether.

The Alfifi

Zed cord

Custom sewn loops for your hooks

Aid ladders

Innovative Gear - Traverse Equipment

Traverse Equipment is Charlie Lane, out of Bellingham Washington. Charlie offers a cleverly designed backcountry ski repair kit that should be able to handle just about any repair. In addition, he has a video going over the kit, and their partner Cascade Mountain Ascents has a very detailed article about the kit components and how to use ‘em.

This section of Alpinesavvy highlights small companies, inventors, artists and other superb humans who make exceptional climbing-related gear.

If you know a company that belongs on these pages, please let me know.

I don't get any sort of advertising fees / benefits / kickbacks from these pages. I simply want to showcase cool companies to a wider audience.

Occasionally these companies may give me a product to review. If that happens, I’ll tell you.

Listings are alphabetical.

The Traverse Equipment ski repair kit

Traverse Equipment is Charlie Lane, out of Bellingham Washington. Charlie's main product: a very thoughtfully designed backcountry ski repair kit.

Traverse Equipment website

Traverse Equipment Instagram, @traverseequipment

You carry a first aid kit for your body. You also need a “first aid” kit for your skis. The proper tools, along with some occasional MacGyver-like creative repairs, can probably get you back to the trailhead, or maybe even continue a multi-day tour.

Not bringing a repair kit? You minor problem could suddenly become a major big deal.

Fortunately, Traverse Equipment has you covered - they sell a very refined ski repair kit that should cover most basic repairs. For longer tours you may want to take a few more things.

In addition to the kit:

Their research and development partner, Cascade Mountain Ascents, has an incredibly detailed repair article on their website that goes through every piece of equipment in the kit and talks about some ingenious ways to make some major repairs. Even if you have a kit already, I'm sure you'll learn a few new crafty tricks to fix your gear by reading this article.

Charlie has a nice YouTube video showing the purpose for everything in the kit, link below.

What's in my pack: ski touring gear by Graybird Guiding

What does a pro ski guide take for a day tour? Check out this detailed list from Shane Robinson and Graybird Guiding.

This post come from Shane Robinson and Graybird Guiding, a Seattle based guide company that not only leads some sweet ski trips, but also has an Instagram full of solid tips. Connect with them at their website and on Instagram. Check out their hashtag #sknowmore for specific backcountry ski tips.

In the pack:

Mountain Hardware 40 liter pack. It’s big enough for a full guide kit or bigger ski mountaineering objectives but can compress down for more average days. Bonus: helmet fits inside most days.

trauma kit (cpr & extreme bleeding) separate from first aid kit and more accessible

general first aid kit

Alpine Threadworks rescue sled & bivy

downhill gloves

headlamp

puffy coat for added warmth or as an emergency layer

Trew Gear Anorak shell

extra buff

helmet

goggles

extra wool hat

thermos for hot water/tea

rescue shovel

probe (ideally 300cm long)

Leatherman multi-tool

sunscreen & lip balm

snow saw, with teeth that can also cut wood if needed in an emergency (not pictured)

Garmin InReach (not pictured)

cordelette, double length sling, and a couple carabiners (not pictured)

Actually wearing:

hat with visor

sunglasses

avalanche transceiver

vRigger - Rope rigging software

Calling all rope nerds and gear heads: check out vRigger! It’s specialized and very cool software that lets you design, test, and teach rope rigging. Here’s an overview of how it works, and a discount code when you’re ready to try it yourself.

Full disclosure: vRigger sent me this software for free. That in no way biases my review; it's a cool product and I want to tell you about it. There are no ads, affiliate marketing or paid product promotions on Alpinesavvy. When I get a free product like this, I’ll always let you know.

vRigger offers a 10% discount to Alpinesavvy Premium Members. Learn about Premium Membership here.

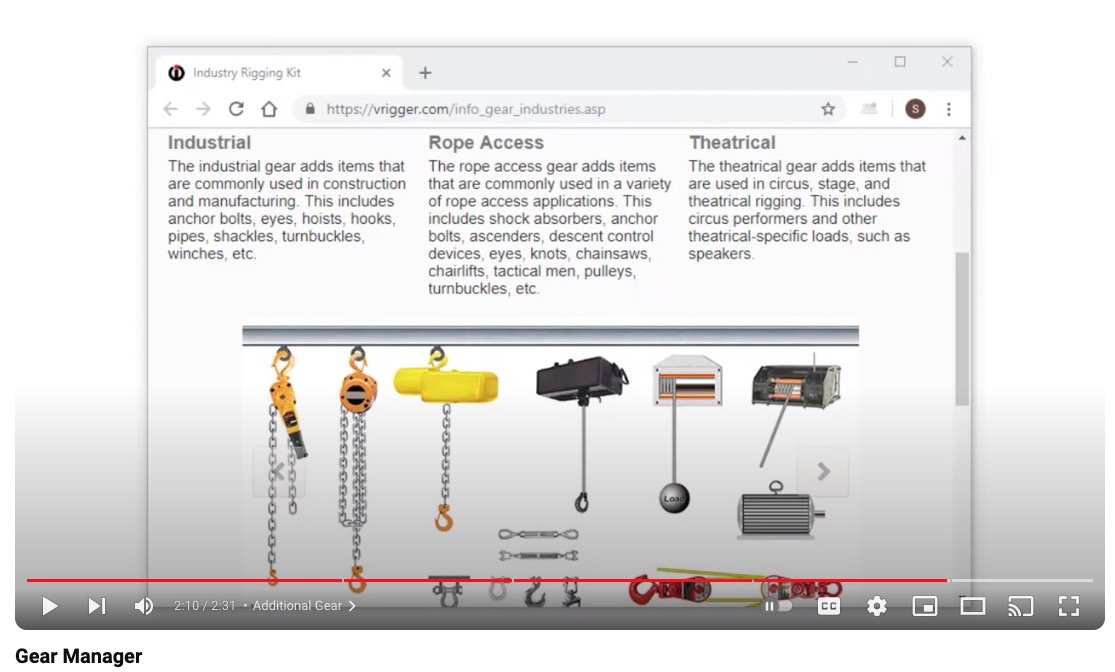

What’s vRigger? Very cool Windows software that lets you design, teach, and test rope rigging.

It may appear that it's a drawing program. But the real power under the hood is the ability to specify load and pulling forces to see how your system actually behaves in the real world.

They have a nice series of tutorial videos showing how to use every part of the software.

The “Getting Started” video is a good overview, to see if it's right for you.

I use vRigger in two main ways:

Setting up different mechanical advantage hauling systems to see the efficiency and forces anywhere in the system.

General purpose drawing and diagrams relating to rigging.

You can insert carabiners, pulleys, rope grabs, friction hitches, etc. to build just about any kind of rigging or hauling system you can dream of. They have a large “library” of pretty much every sort of rigging device available. (And, if they don't have the exact piece that you need, you can create it yourself.)

Drag one component on top of another, and they auto-magically snap together to build your system.

For example, here's a diagram that I made for an article on the three types of mechanical advantage (illustrating that a theoretical 2:1 will always be less in the real world, because of friction, rope stretch, and other hard to quantify variables.)

This shows the difference in efficiency in a 2:1 haul system, between using a pulley on the left and a carabiner on the right.

After you specify the weight of the load (here 100 kg, you can use ‘Merican freedom units as well) it automatically calculates the forces involved all throughout the system, depending on the rigging and load! Cool!

An interesting take away from this diagram: using a lower friction pulley is more efficient to move the load, but it also puts a higher load on the anchor. It's one thing to read about this in a theoretical way; it's another to see the actual numbers like this.

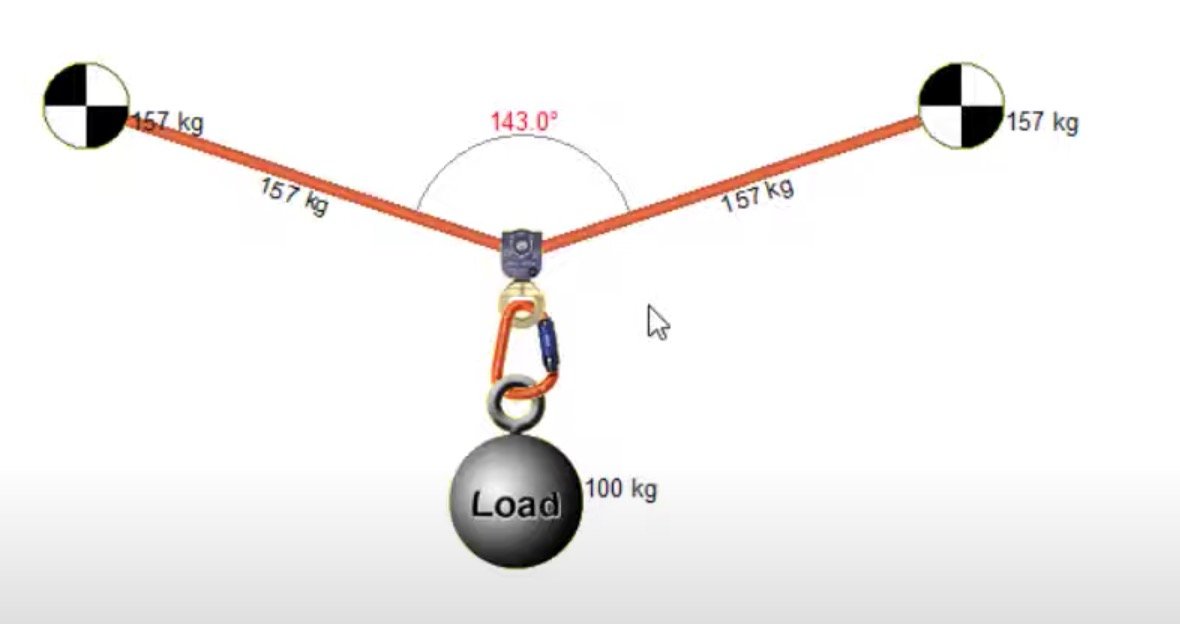

Here's something all climbers should know about: how changing the angles of your anchor “arms” can change forces on the anchor. These numbers dynamically update and change as you click and drag the anchor around.

Hint, you should never build a climbing anchor like this! You can see that there's no more load sharing, but in fact load magnification. If you ever make a Tyrolean traverse, be sure the anchors on either side are unquestionably strong, because they're gonna get a big load!

image: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CRxd2NPDpcw

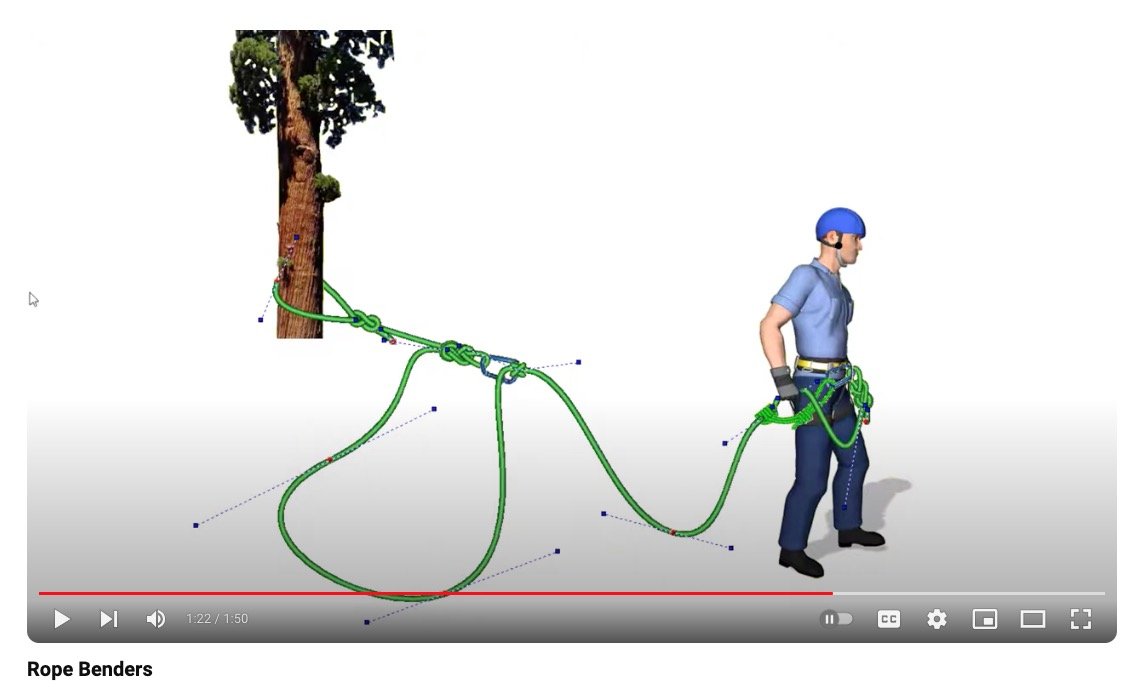

It’s not all engineering stuff. You can make more general purpose diagrams like this. Click and drag on the points and lines to create bends in the rope.

image: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gWBWtQzHwQc

There is a very convenient section of “sample files”, which are essentially premade diagrams for common rigging. This is a big timesaver. Here's an example, some typical mechanical advantage set ups.

There are even gear libraries for specialized applications such as industrial, rope access and theatrical.

So, that's a quick overview of vRigger. While I’m only using a small portion of the capabilities, hopefully you get a sense of how helpful is it for visualizing, drawing, and determining forces of different rigging systems.

If you want it yourself, use the discount code “AlpineSavvy” when ordering for a 10% discount.

Grivel Clepsydra S - the best carabiner for glacier travel?

For glacier travel, it's usually best practice to clip, not tie, to the rope. The Grivel Clepsydra carabiner just might be the best tool for the job: the twin gates will never freeze or jangle open, and the keeper gate prevents cross loading. Plus, it has a bonus feature as part of a minimalist hauling system.

The Grivel Clepsydra is a very unique carabiner. It has a few features that make it perfect as your clip-in for glacier travel. (It comes in two sizes; here I’m featuring the small (S).)

Why is the Clepsydra S great for glacier travel?

No chance of cross loading means you only need one carabiner to clip to the rope

Unique Grivel twin gate means it’s always secure, can’t freeze shut, and can’t wiggle open during a day of glacier tromping. (Yes, the twin gate takes a little getting used to, but you'll figure it out.)

You can use the small end as a prusik-tender in a hauling system (photo below)

Small, fairly lightweight

When you’re not glacier climbing, it works perfectly with a Grigri, as the little “horn” prevents the carabiner from being cross loaded

The standard recommendation for clipping to the rope for glacier travel is to have two opposite and opposed carabiners, at least one of them locking. With the Clepsydra, you only need one.

Before I got this carabiner, I used the Black Diamond Gridlock. This works pretty well, but the screwgate can loosen up over a day, plus as an HMS carabiner, it’s larger than necessary.

Here's how to use the Clepsydra as a “prusik minder” in a hauling system. The small end of the Clepsydra keeps the prusik hitch from being pulled through.

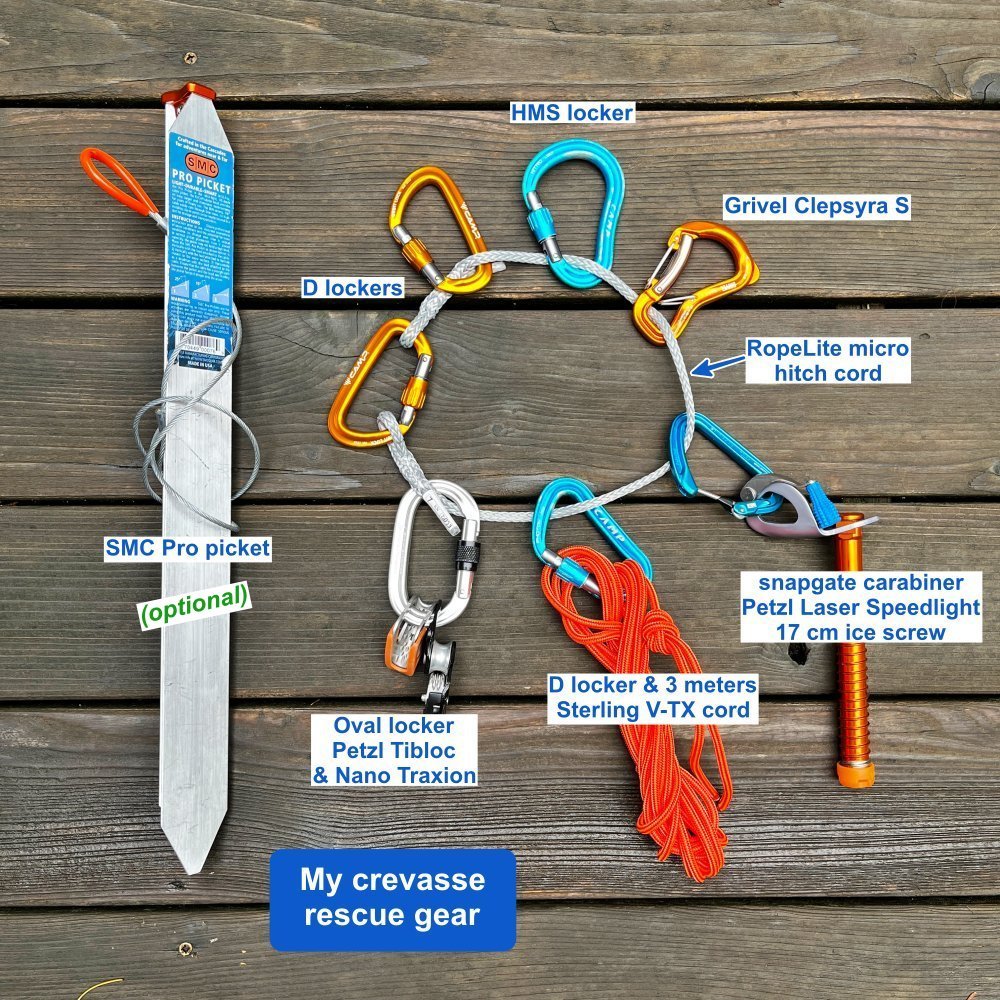

My crevasse rescue gear

There are many approaches to crevasse rescue and many choices for what gear to bring. You need light weight, multifunction, and hopefully have teammates with similar kit to have an effective rescue. Here's my go-to crevasse rescue gear.

There are many different approaches to crevasse rescue, and a near infinite combination of gear that you could carry. The basic requirements are 1) being able to climb the rope if you fall in, and 2) rescuing your partner if you’re the lucky one on top, and they can’t climb out. Fortunately, modern tools and techniques lets you do both with a minimum of gear and weight.

The gear requirements can change depending on team size and general skill level, but here’s a pretty good starting point.

This is pretty much the bare minimum. The idea is with a three of four person team, if everyone carries more or less the same basic kit, rescuers can combine gear as needed.

If you're on a two person team (which is generally considered experts only) you might want to carry a few more items, like maybe another locker, or a120 cm sling.

My crevasse rescue gear

6 locking carabiners: Grivel Clepsydra S, Black Diamond oval, large HMS and three “D” - The Clepsydra works great to clip yourself to the rope, because you can never crossload it, and the gate is very secure. Also works as a progress capture with a a prusik, if you don't have any progress capture pulley like a Traxion. The oval locking carabiner is a time-tested workhorse, and plays well with devices like the Traxion and Tibloc. A larger HMS locking carabiner is helpful if you need to clip other things to it. Finally the D lockers covers any other secure connection you might need. (Yes, I probably have one more locker than I need, but Murphy's Law of rescues is you always need one more locking carabiner.)

1 small snapgate carabiner - you need to rack your screw on something. You can use a non-locking carabiner for non-critical connections, such as the “tractor” in a 3:1 Z drag.

Petzl Tibloc - handy and lightweight ascender and rope grab.

Petzl Nano Traxion (or Micro Traxion) - the modern standard for crevasse rescue gear. Yes, they are expensive, but so helpful in so many situations, they are pretty much becoming everyday carry.

17 cm aluminum Petzl Laser Speed Light ice screw - if you can get down to ice, this can be your anchor on the top. If you fall in, you might be able to place the screw and clip yourself to it to take your weight off of the rope, which can make life for your partners on top a LOT easier when they set up the rescue. Don't bring a screw shorter than about 16 cm.

About 3 meters of Sterling V-TX cord - typically used for equalizing a second anchor, ascending a rope, or securing yourself to the rope system. (Amazing cord; 5.4 mm and rated 15 kN). You don’t need the standard (7 mm 6 meters long) cordelette on a glacier.

Short friction hitch - for climbing up the rope if you fall in, and for making a “tractor” on your hauling system. Here I’m using a spliced eye 5mm hitch cord, which grips well on 6 mm rope. This is made by a cool company called RopeLite; check ‘em out for custom spliced ropework solutions. (There are many other options, such as a loop of 6mm cord or a Sterling Hollowblock.)

What about that picket? Pickets can be very helpful in building a snow anchor but they're not required. Pickets are commonly carried in North America, South America and New Zealand, but not so much in Europe. A more minimalist approach involves making a T-slot anchor with your buried ice axe, skis, or backpack. But to me the axe is a crucial piece of gear, and I'm not too excited to bury it in the snow in case I need it for something else.

When I do carry one, it's the SMC Pro Picket. This is reasonably lightweight, has a pointy end for going into the snow and a reinforced top for bashing on with a hammer. The nicest feature is a permanently attached metal cable on the middle hole, which is how pickets have maximum strength in either vertical or horizontal placements. (That means you need one less 120 cm sling.)

What I don’t bring: pulley, belay device, several “just in case” extra carabiners, designated waist or leg prusik loops. Need another pulley? Grab the Traxion from your partner. Need to rappel or give someone a belay? Use a Munter hitch on your HMS carabiner. The carabiners above are more than enough. And forget those old-school designated waist and leg prusiks; you can easily ascend a rope with the gear shown above.

Where to carry this gear? You want the gear you need to climb a rope easily accessible on your harness or pack gear loops, not inside your pack. For ascending a rope with the gear shown here, I’d keep the orange cord and the oval carabiner with the Tibloc and the Traxion on my harness at a minimum. The rest can probably go inside your pack. I’d also keep the screw on my harness. If you fall in, you might be able to place it and clip to it, removing your weight from the rope as mentioned above.

Harness: A minimalist mountaineering harness, I like the Petzl Tour. Leave that sport climbing harness with the five gear loops at home. You want lightweight, no padding because you have on lots of clothes and (hopefully) are not gonna be hanging in it, with leg loops that open so you can easily put it on while wearing crampons or skis.

Rope: Varies on team size and skill level. Good options include:

30 meter, 6 mm Petzl RADline

40 meter, 7.7 mm Sterling Dyad

50 meter, 7.1 mm Edelrid Skimmer (which is currently the lightest dynamic rope on the market)

The diameter, length, and static vs. dynamic issue of the “best” rope for glacier travel is a BIG topic. Here's a link to some articles on my website that take a closer look. 1) Petzl 6mm static RADLine, 2) static rope for glacier travel.

So, that's my kit. Simple, lightweight, everything has a function. With this I can build just about any flavor of mechanical advantage hauling system I might need, like a 2:1, 3:1, and 6:1.

Some examples of 6:1 systems are here.

Minus the picket, this is what everything weighs.

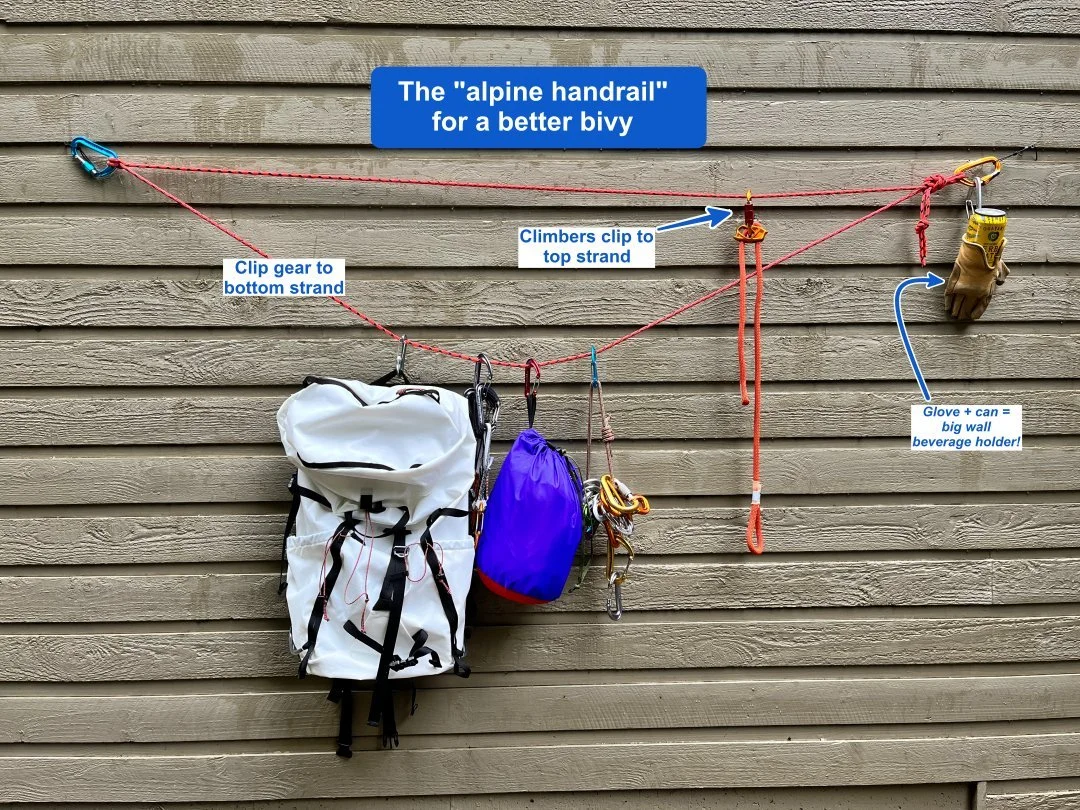

Use the "Alpine Handrail" for a better bivy

The alpine bivy - like camping, only different! If you're spending the night on a small-ish ledge, here's a great way to secure both yourself and your gear.

Credit for this tip: blog post from Andy Kirkpatrick, shared with permission.

If you're spending the night at an exposed ledge, you hopefully have some room to move around and also to organize your gear. You want to do both without any concerns of falling off or dropping anything.

One solution: the “alpine handrail”.

Build a second anchor off to one side of your ledge away from the main anchor. It's ideal if these anchors are bolts. If not, be sure the anchor can take a sideways pull.

Tie a B I G figure 8 on a bight with a loop that's big enough to reach both anchors. In the photo I'm using a cordelette. On a larger ledge, use your climbing rope. Or tie two cordelettes together; get creative.

Tie two additional knots, and clip those to each anchor. In the photo on the left we have a clove hitch, which makes it easier to tension in the top strand.

Now you've made a sort of two story handrail. Make the upper rail fairly tight and the bottom one looser.

Use the upper rail to clip yourself with a tether, and the bottom rail to clip all your gear. You can move along the top rail without having to unclip to move past anything (other than your partner).

Because you made a loop, if any anchor fails, everything won't slip off of one end of the rope.

But what about that horizontal rope strand on the top? Doesn't that make sort of an American Death Triangle (ADT) / vector pull, maybe putting a large load on the anchors?

Excellent question! Short answer is yes, it kind of does, but it should not be a concern if you're on a reasonably sized ledge. That top strand is only if you make a careless stumble, or to keep you stable when you're sleeping.

If you are at a full hanging belay, where you’re putting a real load on the anchor all the time, you want to have a more typical anchor with a distributed load, NOT like this.

Besides, the so-called “death triangle” is probably not as bad as you think. Here's a whole article on it.

Extra points for using your climbing glove as a secure spot to hold your well-earned canned beverage. =^)

Double rope rap: clip tether carabiner to the “pull” strand

“Dang it, which rope strand do we need to pull, I forgot!” Here's a simple way to remember. As you start your double rope rappel, clip your tether carabiner to the rope that needs to get pulled.

For a double rope rap, of course it’s super important to pull the side that has the knot!

Nine times out of ten, you’ll be able to remember just fine. But for multipitch rappels, when you’re threading the lower anchor before pulling and swapping the rope that gets pulled every time, it’s dark, you’re tired after a big day, the weather is challenging, adrenaline-induced brain shrinkage, or whatever, this tip gives you one less thing to pay attention to.

After you unclip your tether carabiner from the anchor, clip it onto the rope that needs to get pulled (here, that’s green).

The carabiner politely slides down the rope above your device. At the bottom, there’s no question about which rope needs to get pulled; it’s always the one with your tether carabiner.

This isn't just for the last person. If the first person down does this, they can start threading the correct pull rope through the lower anchor.

Note: in the photo, I decided to not show a rappel extension to more easily see the rigging. Typically I use a rappel extension and third hand back up.

Faster rope flaking - over your back

Here's a simple way to quickly flake your rope. Simply pull it over your back and shoulder and down into your pack, tarp, rope bag, or whatever.

Want to flake your rope in a hurry, like into a backpack, tarp, or rope bag? Here's one good method if you don't have something to clip the rope to.

If you have any sort of high point around, it’s probably going to be faster to clip a carabiner to that, clip the rope through the carabiner, and then pull downward to stack it.

One other benefit: you usually work most of the twists and tangles out of the rope when you do this.

If you have twists in the rope, run the rope through a ATC style belay device on the high point to help remove them.

It's good to have a shirt or jacket with a hood on it, because you might get a little rope burn on your neck if you don't, ouch.

Another technique that's occasionally used: clipping a carabiner to your helmet strap and running the rope through that. It's probably because I'm not very coordinated, but the few times I've tried this, I end up slapping myself in the face with the rope, so that's not my favorite method. :-)

image credit, shared with permission: https://www.instagram.com/climbing.technical

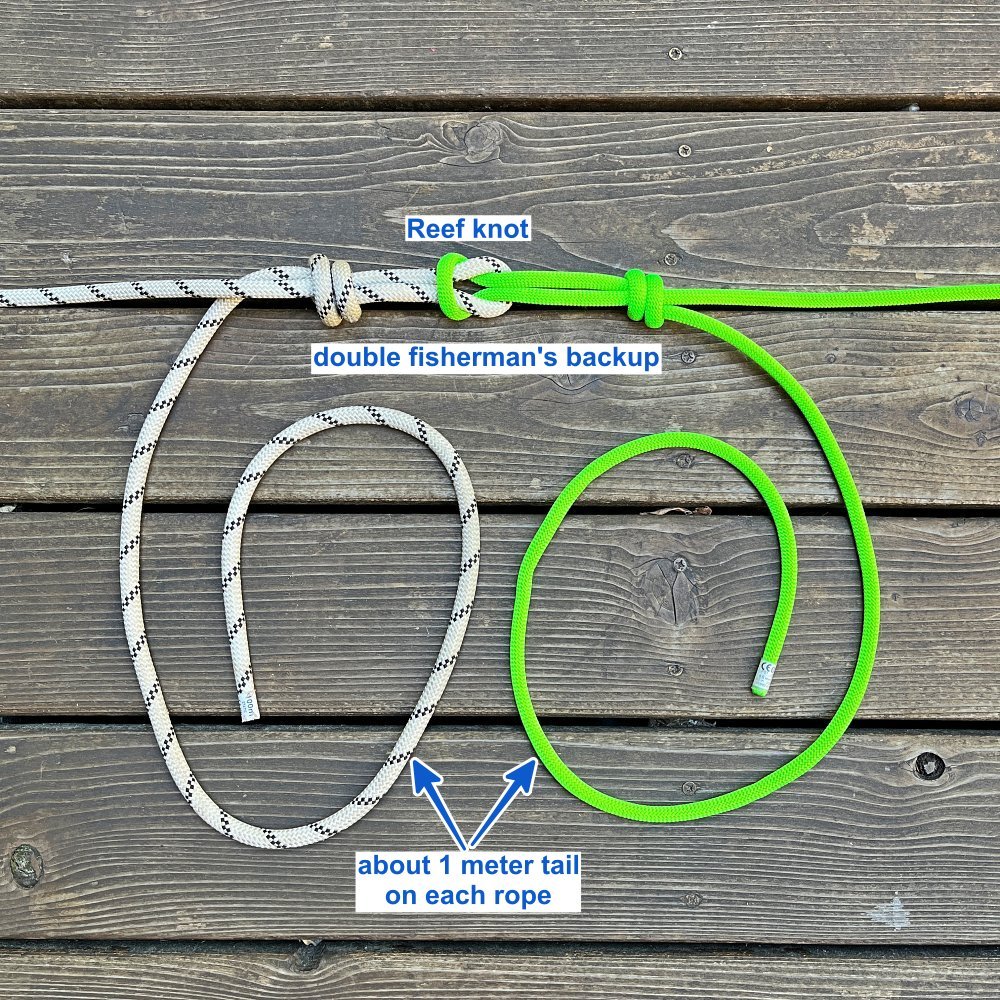

Passing a knot when hauling

Want to lead a few pitches on a big wall, and then do one long haul to bypass an intermediate anchor or two? Here's a crafty way to connect two or more ropes to do this, and easily get that knot through your hauling system.

Credit for this tip goes to Andy Kirkpatrick. It’s from his outstanding book: ”Higher Education: A Big Wall Manual”.

Note - This post discusses techniques and methods used in vertical rope work. If you do them wrong, you could die. Always practice vertical rope techniques under the supervision of a qualified instructor, and ideally in a progression: from flat ground, to staircase, to vertical close to the ground before you ever try them in a real climbing situation.

This might be a seldom-used technique in your toolbox of big wall trickery, but it can sure come in handy for one main thing: it lets you do extremely long hauls, with two or more ropes tied together, allowing you to skip intermediate anchors. For example, you could lead several pitches and then do one L O N G haul.

What’s the problem you need to solve? You have two ropes tied together with a knot that can’t pass through your progress capture pulley / Traxion. This means the knot (which is under a lot of tension) needs to be untied somehow without losing your haul bags.

(Note, if you're hauling with a 2:1 “pig rig”, passing a knot is really easy, because you already have about half the system in place. For this example, we’ll assume a 1:1 haul.)

There are several ways to accomplish this. Here's one that's pretty straightforward. Credit for this technique goes to Andy Kirkpatrick and his excellent big wall book “Higher Education”, definitely recommended.

Before we get into the technique, here’s a favorite related quote from Andy K:

“Hauling is potentially one of the most dangerous aspects of big wall climbing. This translates to ultra-caution in all parts of your hauling system and interaction with bags, haul lines, docking cords, and pulleys. If you rush and make a mistake, drop a load or have it shift where it's not wanted, you could easily kill someone or yourself. I try and teach climbers to view their bags as dangerous creatures, like a great white shark, rhino, or raptor that is in their charge. The ability to keep them calm and under your control comes down to paranoia, foresight, and heavy respect for the damage they can do.”

First, you need to join the ropes with a knot that won’t get welded under a heavy load, perhaps multiple haul bags. Try using the reef knot, backed up with a double fisherman’s, and a long tail of about 1 meter, as shown. There are certainly other options. This one is simple, easy to check, and works well.

It's critical here to leave a minimum of 1 meter tail on the ropes, as shown. (You actually only need it on one strand. But, so you don't screw it up, it’s simpler to make a long tail on both strands.) If you're not sure if you have enough tail, make it a bit longer.

We’re hauling on the white rope. Stop when the joining knot gets about 10 cm / 4 inches from your progress capture pulley. Don’t yank the knot into the pulley!

Get out some more gear: two lockers, a 30 cm (or so) sling, and an ascender. (Instead of the ascender, you could also use a friction hitch, but make it a good one.)

Clip the ascender upside down to the loaded rope. Clip the other end of the sling to the anchor. Here we’re using the Grivel Vlad on the master point, a combination locking carabiner and rigging plate, very helpful for this procedure. A quad, or other type of anchor rigging that gives you several different connection points, works too.

Next, pull up a bit on the white rope, release the cam on the Traxion, and slowly transfer the load onto the ascender. Once you do this, re-engage the cam on the Traxion to back up the ascender.

Notice how doing this creates slack on the knot, yay!

Safety step: tie a bight knot in the end of the green rope and clip it to the anchor with a locker. This ensures the ascender is backed up before you do the next step.

Sweet, you have slack on the knot, and the system is backed up. Now you can untie that reef knot that was joining the ropes. (Give yourself a high-five because you picked a knot that was so easy to untie. =^) Remove the white rope from the system; careful, don't drop it!

Carefully remove Traxion from the carabiner, load the green rope into the Traxion, and untie the backup bight knot. If you feel lucky and are comfortable with the ascender holding the entire load for about two seconds, you can keep the Traxion clipped onto the anchor and push the end of the green rope through the device. I'm showing a bit more conservative, less risky method.

Remove the ascender and sling from the system.

Schweeeeetness, Give yourself a high five, you're done!

All the load is now on the green rope with no knot. Now all you have is 60 more meters of hauling, lucky you!

How can rope drag increase your fall factor?

The theoretical definition of fall factor doesn’t account for rope drag, which can reduce the effective length of rope that’s actually absorbing the force of the fall. So, in the real world, even if you have a lot of rope between you and your partner, you still might need to be concerned with a high factor fall.

Fall factor is a fundamental concept in climbing. It’s mentioned in most all the books, and hopefully you learned it on your first day leading.

Short version:

If you take a fall close to the belay without much rope to absorb the force, you can take a high fall factor. Bad!

But as you get higher on the route, there's more rope in the system to absorb the force of a fall, so fall factor becomes lower, which is good.

However, similar to mechanical advantage, there is a “theoretical” version and an “actual” version, and they can be quite different. Let's take a closer look.

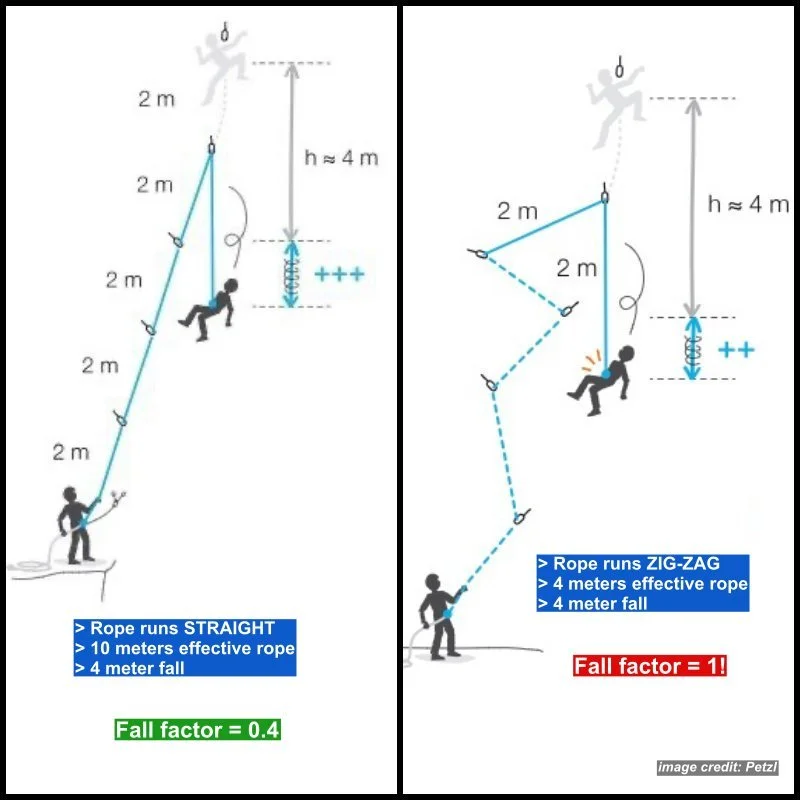

image credit: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Fall-factor-and-impact-force---theory?ActivityName=rock-climbing

First, let’s look at the theoretical definition of fall factor.

Fall factor is a way to look at the the relative impact force of a fall. It's a ratio, calculated by dividing the fall distance by the amount of rope between the belayer and the climber.

In normal climbing scenarios, this will always be a number between 0 and 2. (You can’t have a factor 2 fall on a single pitch climb, because you hit the ground, OUCH!)

The higher the fall factor, the greater the impact force on the climber and gear.

Takeaway: a lower fall factor is better!

Let's have a look at the diagram above, from the always awesome Petzl website. In both cases, the lead climber falls a distance of 4 meters.

In the left example, the 4 meter fall is divided by 10 meters of rope, which gives a relatively low fall factor of 0.4. That means low forces all the way around: on the belayer, the climber, and the top piece of gear. That's good!

Compare that to the diagram on the right. The climber takes a fall of the same distance, 4 meters, but in this case it's right off of the belay on a multi pitch climb, without clipping any gear, with only 2 meters of rope between him and the belayer. This results in the highest possible fall factor of 2, which puts very large forces on the entire system. That’s bad!

How rope drag affects the “actual” fall factor

If you’re leading with lots of rope out, you might think that fall factor should not be a concern. “Schweeeeeet, I've got 30 meters of rope between me and my belayer. If I fall, all that dynamic rope will give a nice soft catch, so no worries about a big fall factor, right?”

Well, that would be true according to the theoretical model of fall factor. But what about rope drag? How does that affect the theoretical model?

There are two reasons why rope drag is bad.

One of them is pretty obvious: you need to work a lot harder to pull up the rope.

But there’s another, less appreciated and perhaps more important reason: rope drag can increase the actual fall factor.

How does this work? I can't say it better than the Petzl website:

“The theoretical fall factor does not take into account the rope friction against the rock and in quickdraws. This friction prevents the rope from stretching over its entire length. Thus, only a part of the rope (solid line) will absorb the energy of the fall: this is called effective rope length.”

In the diagram below, the lead climber has a lot of rope drag because of the zigzagging route. Even though the leader has 10 meters of rope out and they take a short fall of only 4 meters, that short fall is effectively being absorbed by only 4 meters of dynamic rope (the solid blue line) , which gives a relatively high fall factor 1, ouch!

(Granted, the diagram below shows some pretty extreme rope drag. In more normal climbing with moderate rope drag, you would be unlikely to get a factor 1)

That could easily be enough force to rip marginal gear out of the rock, injure the climber, and put a big strain on your rope. This can especially be a concern when aid climbing, where you’re often placing small gear that may not hold much more than body weight.

Petzl did some real live-body testing on this; see the article and results here.

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Fall-factor-and-impact-force---theory?ActivityName=rock-climbing

The “theoretical” fall factor has an equation like this, based on rope length between belayer and climber:

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Fall-factor-and-impact-force---theory?ActivityName=rock-climbing

The “real” fall factor has an equation like this, using the length of rope that is effectively absorbing the force of a fall.

image: https://www.petzl.com/US/en/Sport/Fall-factor-and-impact-force---theory?ActivityName=rock-climbing

Here's a similar diagram from the excellent book “Higher Education” from Andy Kirkpatrick.

Andy notes that with lots of rope drag on the left, we have a higher peak force over a shorter time (bad). With minimal rope drag on the right, we have a lower peak force absorbed over a longer time (good).

Also note that in the zigzag example on the left, there's basically no force felt by the belayer when the lead climber falls. Typically upward displacement of the belayer can absorb a significant amount of force in the system, but here it's not happening at all.

image: Andy Kirkpatrick, “Higher Education” used with permission

How can you avoid rope drag?

A properly bolted sport climb should not zigzag too much, so this generally should not be a big issue when clipping bolts.

For traditional climbing, when you're placing gear, bring a good selection of 60 cm and maybe a few 120 cm sewn slings, and extend your gear as needed to keep the rope running as straight as possible. Doing this minimizes rope drag and allow your rope to do its job properly, absorb the falling force along most of its length.

Climb shorter pitches. If the leader has lots of rope drag, might be time to build a belay (ignoring where the next “anchor” should be.)

Use double ropes. With proper clipping technique, even a zigzag route can be adequately protected and rope drag minimized.

Why bother learning advanced techniques?

A good approach when learning climbing: have a small selection of standard techniques that you know 110%, that you use pretty much all the time. However, when your experience and skill increase, it can be good to have more tools in the toolbox in the rare event you might need them. Here's a great quote from Andy Kirkpatrick on this.

“I already know how to build an anchor, set up a rappel, and belay in the normal way. Why should I learn . . .

Five different ways to set up a top rope anchor?

Rappel with a carabiner brake?

Belay from above with a Munter hitch?

Ascend a rope with a prusik tied with a shoelace?”

British expedition and big wall climbing expert Andy Kirkpatrick has an answer, from his outstanding book, “Down”: